Blog

ISO system expansion = substitution

September 22, 2014 by Bo Weidema

When systems have more than one product, the ISO standards on LCA recommends avoiding partitioning/allocation of the system by instead “expanding the product system to include the additional functions related to the co-products” (ISO 14044, clause 4.3.4.2).

I am sometimes asked: “Is this ‘system expansion’ of ISO not something different from the ‘substitution’ approach (also sometimes described as the ‘avoided burden’ approach) used in consequential LCA?” This lack of clarity in the ISO standards is also sometimes lamented in the literature, e.g. by Brander & Wylie (2011).

This makes me miss the very clear Figure B.2 that we had in the original ISO 14041:1998 (which was merged with ISO 14042 and 14043 into the current ISO 14044 in 2006). This figure illustrated clearly that the authors of the ISO 14040 series viewed system expansion as a substitution. Unfortunately, the informative annex in which this Figure B.2 was placed did not survive the merger. Since few nowadays have direct access to the original ISO 14041 text, let me share this with you:

EXAMPLE 3: Utilizing the energy from waste incineration.

One of the widely used examples of avoiding allocation by expanding the system boundaries is when utilizing the energy output from waste incineration as an input to another product system.

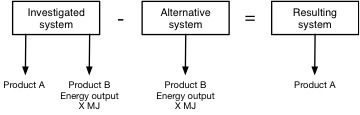

The allocation problem arises because the investigated product system has two outputs: the product or service investigated (A) and the energy output from incineration (B). This allocation problem is often solved by expanding the system boundaries, as illustrated in Figure B.2.

Figure B.2 – Expanding system boundaries for waste incineration

End of quote from ISO 14041:1998

As you can see clearly from the figure, the expansion is done by subtracting the alternative system. Mathematically, subtraction is the same as a negative addition. There are also additional examples of this in Figure 15 and 16 in ISO 14049 (entitled “Illustrative examples on how to apply ISO 14044 to goal and scope definition and inventory analysis”).

But the fact that this discussion pops-up from time to time just goes to show the current ISO 14040/44 sometimes fail us in its role as a standard, that is, to minimize or eliminate unnecessary variation (more about that in Weidema 2014).

References:

Brander M, Wylie C. (2011). The use of substitution in attributional life cycle assessment. Greenhouse Gas Measurement and Management 1(3-4):161-166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20430779.2011.637670

Weidema B P (2014). Has ISO 14040/44 failed its role as a standard for LCA? Journal of Industrial Ecology 18(3):324 326 https://lca-net.com/p/1273

Public hearing of LEAP draft guidelines

July 24, 2014 by Bo Weidema

Last week, I spent 20 hours making more than 30 pages of comments to the three draft guidelines from the FAO Livestock Environmental Assessment Performance (LEAP) Partnership. They are currently in public hearing until July 31st. You can find my comments in our executive club, if you are a club member.

There is already a large number of guidelines that interpret the basic ISO 14040/44 standards for LCA for specific products, countries and/or impact categories. Every time a new one is made, there is the risk of introducing new inconsistencies (see Weidema 2014) although each new guideline sets out with the praiseworthy intention to provide consistency and harmonisation – in the case of LEAP for environmental performance assessment and monitoring of livestock supply chains on a global scale. If we should make comments on all the guidelines that are continuously being produced, we should have a full-time person or more for this task alone. But in the case of FAO, I made an exception – like I previously did with the EU product environmental footprint guideline – since I regard FAO as an important public-service organisation with a large international impact.

And although it was a lot of pages to read and comment – with some unavoidable redundancy due to the three parallel guidelines for feed, poultry, and small ruminants – I found it worthwhile, since the guidelines actually contain quite some default data and assumptions, for example for nitrogen excretion from chicken and laying hens, that will hopefully lead to less arbitrariness when applied in future studies.

But with more than 30 pages of comments you can imagine that I have not been entirely happy with the current state of the drafts. At the most fundamental level, it does not seem wise for an international guideline to adopt an attributional modelling approach that cannot be used for decision support. The main problem of the attributional approach is that the results cannot be used for decision support regarding improvements of the analysed systems, simply because the results do not reflect the environmental consequences of such improvements. The results will be misleading if they by mistake should anyway be used for decision-making. The authors appear to be unaware that an attributional approach cannot say anything about the environmental performance of a product, only about the environmental performance of that part of the product system that is included according to the chosen allocation rules for by-products. This is why ISO 14040/44/49 recommends the use of system expansion to avoid allocation, and generally describes a consequential approach to system modelling. The main reason for this is that ISO 14040/44/49 is intended for supporting improvements, which requires LCAs that provides information on the consequences of these improvements.

And you will probably not be surprised that I am also not happy with the deviation from the ISO hierarchy for handling co-products, where the draft LEAP guidelines m ix system expansion and allocation. Mixing these approaches in the same study leads to the result being neither attributional nor consequential. System expansion is not relevant for attributional questions and allocation is not relevant for consequential questions. Each allocation method provides an answer to a specific question, so when combining several different allocation methods within the same study, both the question and the answer is obscured. Consistently applying system expansion for joint production and subdivision by physical causality for combined production provides an unambiguous answer to the question of the consequences of a decision, which is the purpose of the majority (if not all) LCAs.

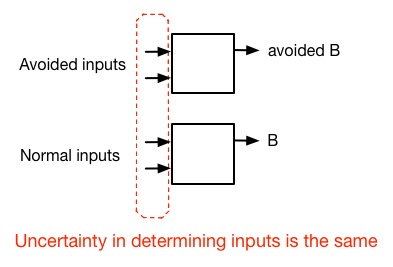

The FAO text here suggests that there are situations where system expansion cannot be applied because the avoided production cannot be unambiguously identified. However, since the input to a market is identified by the same procedure whether the market output is decreasing (avoided inputs) or increasing (normal inputs), the avoided production can always be determined with the same degree of (un)ambiguity as any other market input to the product system. If the procedure that is generally accepted for identifying upstream market inputs is discarded just because the sign of the flow has been inversed, this places into question the entire procedure by which we link our product systems, and can therefore not be used as an argument for not applying the procedure specifically for avoided production.

And then there are all the things that are not included in the guideline even though these are exactly the kind of things that would have been relevant. Such as how to determine the temporal boundary between two subsequent crops with an intermittent fallow period, or how to deal with biogenic carbon (excluded, which is not in line with ISO 14067).

These were just some of the many issues that hopefully will be corrected in the final version. Which is why such public hearings are so important.

Social LCA – new agenda or old ideas?

June 10, 2014 by Bo Weidema

My personal interest in social LCA go way back – to the ideas of the fair trade movement and the ideas of organic agriculture of respecting both humans and nature (my original education was as an agriculturalist).

In the 1980’ies we tried to formulate these ideas in ways that could be measured and certified. Also, the definition of “environment” in the ISO 14000 is very broad, including the human and social environment, and in line with the awareness that the problems in the outer environment cannot be solved in isolation from issues of social change (cf. World Commission on Environment and Development 1987). With a starting point in the definition of a sustainable development given by the Brundtland-commission, a number of the social indicators have now been codified in ISO 26000.

That LCA should include social issues has been part of LCA thinking from the start. The very early framework on LCA developed at the SETAC workshop in Sandestin (Fava et al. 1992) resulted in a list of social welfare impact categories. Fava et al. (1991) also mention that effects on disadvantaged groups (children, pregnant women, minorities, low-income groups, future generations) should have special attention and that the voluntary versus involuntary exposure is a relevant issue. However, the workshops did not give any solution to how these social welfare aspects could be included in a practical product assessment.

It was not until the more general interest in social issues arose with the concept of “Corporate Social Responsibility” that this also returned to the main agenda of LCA (see e.g. my 2002 presentation Quantifying Corporate Social Responsibility in the value chain to the ISO TC207 meeting in Johannesburg). In 2004, the UNEP/SETAC Task Force on the integration of social criteria into LCA was initiated, which finally resulted in the 2009 “Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products”. In parallel to this, ISO 26000 codified “Social Responsibility” which also integrates a life cycle concern.

Right now, the largest hurdles I see for social LCA to become mainstream are 1) To obtain adequately specific and relevant data 2) To adequately describe and quantify the impact pathways to allow comparisons across impact categories.

To bring quantitative social LCA further, there are also a gap to overcome in the communication between the quantitatively focused social engineers of LCA and the often more qualitatively educated social scientists.

So while I believe there are still some hurdles to overcome, I find that by now social LCA has proven itself as a feasible and applicable method for assessing the product life cycle.

References:

Fava, J.A., Denison, R., Jones, B., Curran, M.A., Vigon, B., Selke, S. & Barnum, J. (1991): A Technical Framework for Life-Cycle Assessments. Washington DC: Society of Env. Toxicology and Chemistry & SETAC Foundation for Env. Education Inc. (Workshop in Smugglers Notch, 18-23.08.1990).

Fava, J.A., Consoli, F., Denison, R., Dickson, K., Mohin, T. & Vigon, B. (1992): A conceptual framework for life-cycle impact analysis. Pensacola: SETAC Foundation for Environmental Education (Report from a workshop in Sandestin 1.-7.2.1992).

Weidema B P (2002) Quantifying Corporate Social Responsibility in the value chain. Presentation for the Life Cycle Management Workshop of the UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative at the ISO TC207 meeting, Johannesburg, 2002-06-12.

ILCD handbook situation A or B?

May 5, 2014 by Bo Weidema

At times I get the impression that there seems to be a widespread confusion with the text of the ILCD Handbook pertaining to modelling choices. The difference between the ILCA situation A (so-called attributional) and situation B (consequential) is described as if relates to the size of the decision, as if small-scale decisions have no real impacts.

But if a decision has no impacts, there is no point in modelling it with LCA, is there? If there is an impact, what we are studying is a decision that has a marginal (small) impact. And it is this marginal impact that we should then try to model. This is exactly what we do with consequential modelling.

So it seems strange that the ILCD Handbook limits the use of consequential modelling to larger decisions, which are maybe not even marginal! Now, what the ILCD Handbook calls “attributional” in relation to decision situation A (micro-level decision support) is in fact not what is normally understood as “attributional”. UNEP/SETAC in their 2011 Global Guidance Principles for Life Cycle Assessment Databases describe the “attributional approach” as an attempt “to provide information on what portion of global burdens can be associated with a product (and its life cycle)”.

In theory, if one were to conduct attributional LCAs of all final products, one would end up with the total observed environmental burdens worldwide. This is not the case with the modelling described in the ILCD Handbook for decision situation A. Since the model operates with substitution (“system expansion”), the sum of the LCAs of all products in the economy will not add up to the total burdens.

Substitution is a technique you use when you want to study the small changes caused by a decision. And many small changes of course do not add up to the total of all existing burdens, because not everything changes. So from this perspective, the ILCD Situation A model is in fact rather consequential.

Put very shortly, the only difference in the described modelling for situation A and situation B is that the situation A model uses averages as inputs to the markets, while the situation B model uses only the inputs from the marginal suppliers. However, this difference cannot be justified by the size of the decision to be taken. A small decision does not have average consequences, no more than a large decision. A small decision has only marginal impacts (since the word marginal in this context exactly means small, that is: the things that change when you make a small decision…).

In conclusion, I do not find any situations that (are small enough to?) justify the use of the model described for the “Situation A” and therefore recommend in general to always use the model for “situation B” as soon as you are studying a decision that involves a change. I hope my above explanation provides adequate justification for this recommendation. If not, let me know.