Blog

Party spoiler

April 23, 2015 by Bo Weidema

In what was announced as a celebration of the first 3 LCA guidelines for feed, small ruminants and poultry (http://www.fao.org/partnerships/leap/en/ ) of the FAO LEAP Partnership, I had to play the role of the party spoiler. Practically all the speakers talked about how these new guidelines would allow the identification of hotspots and options for improvement. At the same time it was made quite clear that the guidelines are for attributional LCA, explicitly excluding consequential modelling. Therefore I had to point out that as long as you limit yourself to an attributional approach, where you cut-off (e.g. by allocation) a part of the affected systems, these guidelines cannot be used to consistently identify improvement options. For example, if you by allocation isolate the milk from dairy farming from the meat, you may reach the conclusion (as one presenter showed) that intensification of dairy farming is environmentally beneficial. With a consequential approach, that includes all the real-life effects in the system, you are likely to reach the opposite conclusion, because of the important role of the displaced meat production. So if you really want to take serious all the fine words used to present the 3 guidelines (science-based, consistent and focussed on continuous improvement), your guidelines should support consequential modelling.

Luckily, my caustic words were met by broad agreement to the current limitations of the FAO guidelines, and a promise that there will be a second round that will look at the possibility to provide guidelines that address the LCA methods needed for decision support for improvements, in accordance with the ISO 14040 series of standards.

See also my blog on FAO LEAP from July 2014.

Disentangling E P&L and Natural Capital Accounting

March 4, 2015 by Bo Weidema

Results from lifecycle based environmental assessment are increasingly being expressed through the use of economic terminology. Every second year a new buzzword takes the stage. In this blog-post I try to provide some clarification on two recent buzzwords: E P&L (Environmental Profit & Loss account) and NCA (Natural Capital Accounting).

In 2011, PUMA (the shoe-maker) launched their E P&L, a practice that was followed by several others, including Novo Nordisk and the Danish Fashion Industry. The intention is to complement the company’s normal Profit & Loss account (the financial statement of the income and costs) with an account of the monetarised external benefits and costs related to the life cycle of the product portfolio of the company. Formally, an E P&L should thus be called a ‘Product portfolio E P&L’, which could more lengthily be described as a ‘Product portfolio environmental life cycle assessment with monetary valuation of impacts’. Except for the monetary valuation of the impacts, an E P&L is thus equivalent to what the European Commission calls an Organisation Environmental Footprint (OEF).

In 2013, September 27th, The Guardian had an article stating: “If you are looking for the next big thing in sustainability, you needn’t look much further than natural capital accounting”. Last year, in December, the European Commissions Business and Biodiversity Platform published a guide to NCA (Spurgeon 2014), in which E P&L is mentioned as one possible Natural Capital Accounting approach.

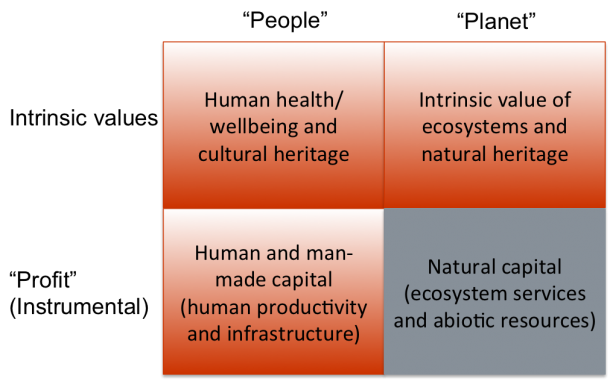

However, capital is essentially a synonym for resources, i.e. those things that enable us to produce goods and services. Natural capital thus covers abiotic natural resources as well as ecosystem resources that provide us with ‘ecosystem services’ – another buzzword that now has been around for 10 years. As such, natural capital only has instrumental value and the term cannot sensibly be used to cover the intrinsic value of nature, i.e. the value that we place on nature in itself and not for what it can produce.

And even more obviously, natural capital cannot sensibly be said to cover the value of the non-natural areas of protection, whether intrinsic (human wellbeing and cultural heritage) or instrumental (man-made and human capital) and thus NCA should never be able to aspire to cover all impacts on these areas of protection.

The below table clearly shows how impacts on natural capital are only a (small) part of the whole picture of environmental impacts. In the table, the different areas of protection are related to the popular “people, planet, profit” concepts.

The NCA guide (Sturgeon 2014) is actually aware of the terminology problem it creates, since immediately after having presented the definition of NCA as “Identifying, quantifying and/or valuing natural capital impacts, dependencies and assets, as well as other environmental impacts and liabilities, to inform business decision-making and reporting”, the guide goes on to say: “To be more technically correct, the definition for NCA for business should only include impacts and dependencies around ‘natural capital’ and not ‘other environmental impacts’.”

The NCA guide (Sturgeon 2014) is actually aware of the terminology problem it creates, since immediately after having presented the definition of NCA as “Identifying, quantifying and/or valuing natural capital impacts, dependencies and assets, as well as other environmental impacts and liabilities, to inform business decision-making and reporting”, the guide goes on to say: “To be more technically correct, the definition for NCA for business should only include impacts and dependencies around ‘natural capital’ and not ‘other environmental impacts’.”

Now we can only hope that the readers come as far as this caveat and do not take the definition out of its context. For my part, I will continue to say that we do ‘Product portfolio E P&L’s and that NCA in its more narrow definition is a part of this.

Reference

Spurgeon J P G. (2014). Natural Capital Accounting for Business: Guide to selecting an approach. Brussels: EU Business and Biodiversity Platform.

Towards a complete set of sustainability indicators

December 7, 2014 by Bo Weidema

The stakeholder approach to sustainability indicator development has led to a plethora of different indicator sets. This makes cross-comparisons difficult and is inefficient in terms of resources that need to be spent on measurement and reporting. Furthermore, important aspects of sustainability may be omitted, either because there is no particular stakeholder interest that defends a specific aspect, or due to concerns for data availability.

An alternative to the stakeholder approach is a more conceptual approach (these approaches are of course not necessarily mutually exclusive) starting from the definition of sustainable development and which in its outset seek complete coverage of what the UNEP/SETAC Working Group on Impact Assessment (Jolliet et al. 2003) called “areas of protection”.

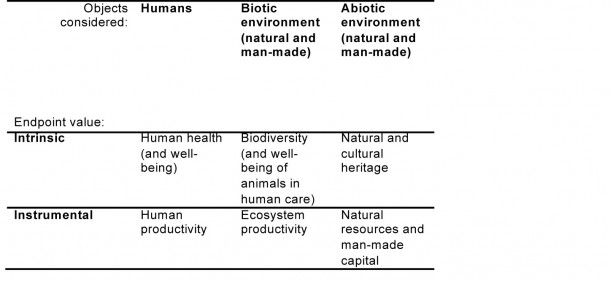

A conceptually complete organisation of “areas of protection” can be seen in Table 1. What I mean by conceptually complete is that any item must be either human or non-human; any non-human item must be either biotic or non-biotic; any value must be either intrinsic or instrumental.

Table 1. Areas of protection in the SETAC/UNEP LCIA framework from Jolliet et al. (2003) slightly modified by Weidema (2006).  You may note that what is here called “Instrumental values”, may also be called “Resources” or “Capital”, and that both human and man-made ecosystems/resources are covered, without necessarily making an explicit distinction (which of course could be done at a next level).

You may note that what is here called “Instrumental values”, may also be called “Resources” or “Capital”, and that both human and man-made ecosystems/resources are covered, without necessarily making an explicit distinction (which of course could be done at a next level).

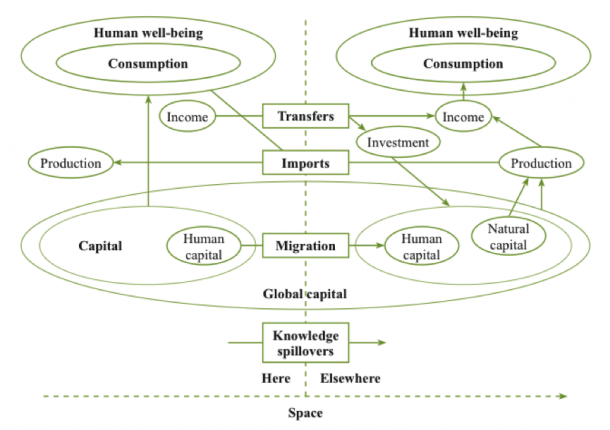

While such a framework provides completeness, it is of course only the first step towards a complete set of indicators. Another recent important contribution in this field, which also has a conceptual starting point, is the Conference of European Statisticians Recommendations on Measuring Sustainable Development (UNECE 2014). In this report, you can find not only a very comprehensive set of sustainability indicators but also a very clear description of the relationship between these indicators and the national accounting framework. The report particularly points out that for each aspect to be measured, both a geographical (imports/exports) and a temporal (capital transfer to future generations) perspective need to be covered. I reproduce below the graph that illustrate the geographical perspective.

Figure on Sustainable development: “here” versus “elsewhere”. From UNECE (2014). The recommendations have been endorsed by statisticians from more than 50 countries and are expected to contribute to the ongoing United Nations processes for setting up Sustainable Development Goals and the related targets and indicators, and defining a post-2015 development agenda.

The recommendations have been endorsed by statisticians from more than 50 countries and are expected to contribute to the ongoing United Nations processes for setting up Sustainable Development Goals and the related targets and indicators, and defining a post-2015 development agenda.

The conceptual foundation and the potential indicators suggested in the UNECE publication may serve as a good starting point for further harmonization of the measurement systems and development of a set of indicators that could be used for comparison across countries, and probably with some adaptation also across individual enterprises and products.

References

Jolliet O, Brent A, Goedkoop M, Itsubo N, Mueller-Wenk R, Peña C, Schenk R, Stewart M, Weidema B P. (2003). Final report of the LCIA Definition study. Life Cycle Impact Assessment Programme of The UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative. Paris: United Nations Environmental Programme. https://lca-net.com/p/1100

UNECE (2014). Conference of European Statisticians recommendations on measuring sustainable development. New York and Geneva: United Nations. www.unece.org/publications/ces_sust_development.html

Weidema B P. (2006). The integration of economic and social aspects in life cycle impact assessment. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 11(1):89-96. https://lca-net.com/p/1024

Creating shared value with Life Cycle Assessment

November 19, 2014 by Bo Weidema

Life Cycle Assessment is not about blaming businesses for negatively impacting environmental or social conditions – rather, it is about identifying leverage points for improving the role of business in society. In many ways, enterprises have the powers to solve issues that societies have struggled with for many years – namely the internalisation of the social (and environmental) externalities.

“Creating Shared Value”, “Net positive” and “Handprints” are some of the existing business concepts that aim to shift the focus from the negative impacts of businesses to the positive force of business in solving societal problems.

Creating Shared Value (CSV) is a business policy and practice that aims to increase both economic and social well-being and business competitiveness based on an understanding of their co-dependence (Porter and Kramer 2006, 2011). “Net positive” is a similar concept defined as adding greater value to society than you take away (Green Mondays 2013), but applied to more specific issues like returning more to nature than you use. Finally “Handprints” is a concept (Handprinter) to measure the benefits a person or an organization can provide, rather than the impacts (social costs) it incurs.

These concepts borrow from earlier ideas of “footprints”, “bottom-of-the-pyramid”, industrial symbiosis, strategic corporate social responsibility etc. but what is excitingly new about these concepts is the radical way they re-formulate the role of business in society; to paraphrase Porter: “to harness the power of capitalism in the service of society”.

An example of this, given by Porter and Kramer (2011), is Vodafone’s pioneering M-Pesa mobile-phone based banking service in Kenya, helping the poor save money securely and increasing the ability of small farmers to produce and market their crops. M-Pesa has become the most successful mobile phone based financial service in the developing world. When introduced in Afghanistan the direct payments proved a tool to combat corruption (Rice and Filippelli 2010).

Essentially, the idea is all about internalizing externalities by creating the markets that are currently missing. Thus, it is actually not capitalism as such that is harnessed, but rather the market economy. In fact, the proposals of Porter and Kramer (2011) do not warrant the strong focus they give to re-inventing capitalism and the role of companies, since these roles could as well be performed by non-profit or public organizations. What is important from the idea of CSV is that the organizations work under the efficiency imposed by a market economy.

In relation to Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), CSV implies an expansion of the scope of social LCA to include the social impacts normally left aside to be handled by government. I believe the addition of the CSV perspective can enhance the comprehensiveness and practical relevance of LCA.

On the other hand I think that LCAs strong tradition for quantitative measurement can contribute a lot to a realistic and credible valuation and prioritization of the opportunities for CSV, enhancing its capability to optimize both social and corporate decision-making.

See also our previous blog on social LCA https://lca-net.com/blog/2014/06/

References:

Porter, M. E., and M. R. Kramer. 2006. Strategy and Society: The Link Between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harvard Business Review December 2006, pp. 78-93.

Porter, M. E., and M. R. Kramer. 2011. Creating shared value. How to reinvent capitalism – and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review January/February 2011, pp. 1-17.

Green Mondays. 2013. Crowdsourced Green Mondays: Net positive. An expert crowd’s view of Net Positive business strategies. www.green-mondays.com/admin/uploads/media/NetPositive (accessed 2013-12-26). This is now a broken link. But see http://thecrowd.me/sites/default/files/NetPositive.pdf

Rice, D., and G. Filippelli. 2010. One Cell Phone at a Time: Countering Corruption in Afghanistan. Small Wars Journal September 2, 6:17pm. http://smallwarsjournal.com/blog/journal/docs-temp/527-rice.pdf (accessed 2013-12-26).