Blog

Consequential LCA is not scenario modelling

March 13, 2016 by Bo Weidema

In the discussion on the differences between attributional and consequential modelling for Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), it is a common misunderstanding that consequential modelling requires scenario modelling or other form of forecasting, and therefore should be more uncertain than attributional models based on average, allocated data from the recent past.

In their pure form, attributional models do not intend to say anything about the future, but it is still very common to find them applied to support claims about what is the best action to take to reduce future environmental impacts. One argument used to defend this (mis)use is the uncertainty argument.

In reality, both consequential and attributional models can be based on data from the recent past:

- attributional models are based on data from the recent past on observed average behaviour of activities,

- consequential models are based on data from the recent past on observed marginal changes in activities (including marginal substitutions).

In this way, consequential models that seek to identify the here and now consequences of decisions do not need any more assumptions (or more uncertain data) than do attributional models.

If dealing with issues further into the future, both attributional and consequential models would benefit from scenario modelling or other forms of forecasting, because future average behaviour, as well as future marginal changes, are different from those that can be predicted by extrapolating data from the recent past.

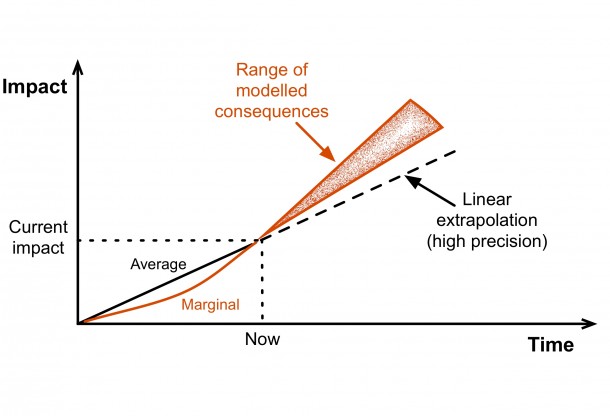

But when choosing forecasting techniques, there is no reason to believe that a precise linear extrapolation of the past average is a better model of the future than a less precise, but more accurate, consequential model. I have tried to illustrate this graphically here:

For more details on the consequential modelling and the differences to attributional modelling, see consequential-lca.org

For more details on the consequential modelling and the differences to attributional modelling, see consequential-lca.org

Don’t take zero for an answer

February 25, 2016 by Bo Weidema

I often encounter the idea that some numbers are just too uncertain to use and that it would be better not to quantify the issue and describe it qualitatively instead. Earlier this month I was presented with another example: At the first meeting of the ISO working group on monetary valuation, one of the environmental economists present used the effects of electromagnetic fields near high voltage transmission lines as an example of an impact that should not be quantified because the knowledge was just too uncertain.

I claimed that uncertainties cannot and should not be an argument for not quantifying. Even when describing something qualitatively instead – placing a flag as some people say – the most likely consequence is that decision makers will leave the issue out of consideration altogether – or maybe even worse: the missing quantification may be used by advocates for special interests to argue that the issue is important – even though a simple quantification of the worst case would have shown that it cannot be.

Another often-stated argument against using uncertain numbers is that decision makers cannot handle uncertainties. But this is simply not true. Uncertainties are a certain part of life – we live with them everyday. As Lise Laurin, CEO of EarthShift, put it in a recent discussion on PRé’s LCA discussion list:

‘We all want to know if it is going to rain on the day of our picnic. But what we get is a probability. If the forecaster says there is a 30% chance of rain, we may go ahead and schedule the picnic but have contingency plans just in case. The only thing we need to know about the process of forecasting the weather is that it’s really complicated’.

And, yes, quantifying environmental effects include a lot of complicated issues – and some of these issues will certainly have high uncertainties. Sometimes our data are just not that accurate, either because the methodology is in its infancy or because no one has bothered to do that thorough study yet. I am a firm believer in presenting data with their inherent uncertainties and not exclude any part of the inventory just because it is complicated.

And, yes, quantifying environmental effects include a lot of complicated issues – and some of these issues will certainly have high uncertainties. Sometimes our data are just not that accurate, either because the methodology is in its infancy or because no one has bothered to do that thorough study yet. I am a firm believer in presenting data with their inherent uncertainties and not exclude any part of the inventory just because it is complicated.

Our role and duty towards the policy- and decision-makers is not to decide that some impact or other have to be excluded, because it has a high uncertainty – but perhaps we need to put more emphasis on educating our customers and stakeholders to ask for completeness and uncertainty in the information they are given – and not to take zero for an answer.

Avoiding “system expansion”?

December 10, 2015 by Marie De Saxcé

When producing a product footprint – or life cycle assessment (LCA) result – we want it as far as possible to be useful for decision support. Therefore, the way we model the product systems should maintain mass, energy and monetary balances intact, fully reflecting physical and economic causalities, based on empirical relations rather than normative assumptions and arbitrary cut-offs. This also implies avoiding allocation (partitioning) of systems with joint production of co-products, since this is an inherently normative procedure that cuts off part of a product system and therefore can provide misleading results.

To avoid allocation of systems with joint production, we use a procedure that the ISO 14044 standard on LCA calls “system expansion”. This makes it sound like something was missing in the original system and that a lot of additional work may be involved. But this is not the case.

When the text of the ISO 14044 standard was originally drafted, before the turn of the century, procedures for LCA were not as developed as they are now. Product systems were manually created using foreground data to painstakingly describe flows to and from nature for each unit process in the product system. Cut-offs were needed due to lack of data or time. In this context, the term “system expansion” appeared natural for describing the inclusion of modelling of the further fate of the by-products and wastes and the resulting changes (substitutions) in the product system, as opposed to cutting them off by allocation.

Today we have environmentally extended input-output (I/O) databases based on national statistics that cover the entire global economy. Our product systems are therefore inherently complete from the outset. When we perform “system expansion”, we therefore do not actually expand the product system, but simply follow the fate of the by-products and wastes within the already complete system, accounting for the increase in treatment activities and decrease of the upstream activities that supply the same markets as the useful by-products. The only manual work left today is to ensure the correct distinction between the products that determine the volume of the joint production and the by-products for which we must ensure that they are correctly linked to the markets where the substitution occurs. More details and examples of this can be found at www.consequential-lca.org.

The term “system expansion” is therefore no longer appropriate for what we do in practice, and we therefore tend to rather use the more general and neutral term “substitution” for this procedure. This is in accordance with the way “system expansion” was described in the original ISO text, as explained by Bo Weidema in a previous blog post.

Consequential vs. attributional LCA

November 19, 2015 by Bo Weidema

I often hear (or read) statements like “Attributional LCA is accounting for the total emissions from the processes and material flows used during the life cycle” which shows a lack of understanding for the large parts of the life cycles that are actually ignored in attributional LCA.

Attributional LCA uses normative cut-off rules and allocation to isolate the investigated product system from the rest of the World. And by this, it ignores a lot of the physical and economic causalities that are related to the life cycle of a product.

The below video (a simple slide-show) explains three of the issues that are included in consequential life cycle models, while not being included in attributional LCA (double-click for full screen mode).

For more information see: consequential-lca.org