Blog

Natural capital from an LCA perspective

August 2, 2016 by Bo Weidema

Last month, on July 13th, the Natural Capital Coalition published their Natural Capital Protocol, which is a framework for performing Natural Capital Assessments “designed to help generate trusted, credible, and actionable information that business managers need to inform decisions”.

Natural Capital is defined as “The stock of renewable and non- renewable natural resources (e.g., plants, animals, air, water, soils, minerals) that combine to yield a flow of benefits to people”. These flows can be ecosystem services or abiotic services, which provide value to business and to society, and thus includes the impacts on human capital that go via impacts on natural capital (e.g. clean air). The Natural Capital Protocol thus covers the same issues as traditional biophysical Life Cycle Assessment (see also my March 2015 blog on the terminology of Natural Capital Accounting).

Figure 1.1 from Natural Capital Protocol (2016). Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The framework largely follows that of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), starting with the goal definition in Chapter 2: “Define the objective” including target audience and stakeholder engagement. The scope definition in Chapter 3 covers the determination of the focus (organizational, project or product), the extent of the life cycle perspective (here called “boundary”: cradle-to-gate, gate-to-gate, downstream), the stakeholder perspective (here called the “value perspective”: own business only, society, and/or specific stakeholder groups), type of valuation (qualitative, quantitative, monetary), and “other technical issues”: baselines, scenario alternatives, spatial and temporal boundaries.

The Natural Capital Protocol continues by describing screening (Chapter 4: Which impacts and/or dependencies are material?), inventory (Chapter 5: Measure impact drivers), impact assessment (Chapter 6 on the measurement of state changes, i.e. impacts), valuation (Chapter 7), interpretation (Chapter 8) and taking action (Chapter 9).

The largest difference to LCA seems to be the particular focus on what the Protocol calls Natural Capital dependencies, which is an optional risk assessment of the supply security and liabilities related to use of Natural Capital and the precautionary measures that the business takes to reduce these security and liability issues. Such a risk assessment should be part of normal business practice, but is not part of LCA, while the practical measures taken will be part of a life cycle inventory and the impacts of these measures are thus included in the LCA results.

For people familiar with LCA, the Natural Capital Protocol may not contain much new, but the Protocol is a good, simple introduction to environmental assessment from a business perspective and an important call for business to take action.

Reference:

Natural Capital Protocol (2016). Available: www.naturalcapitalcoalition.org/protocol

Circular economy – where does that leave LCA?

June 22, 2016 by Stefano Merciai

At the end of 2015, the European Commission adopted a Circular Economy Package (European Commission 2015). The intention is to move away from current linear business models (make-use-discard) to a future of circular business models (reduce, reuse, remake, recycle). “Closing the loop” is the objective for the next decades.

The concept of a Circular Economy (CE) is that of maintaining the value of products as much as possible within the economic sphere. Therefore, a lot of attention is on the last stages of the economic processes, i.e. the treatment of waste. Re-use and recycling should gradually phase out landfills and incinerators. At the same time, the residues, which inevitably leave the economic sphere, should be harmless for the environment.

The implementation of a CE is seen as a challenge that will reshape our economies, affecting positively the entire society, from the economy to the social sphere, from the environment to the human wellbeing.

All these objectives can be considered absolutely noble, doubtless. However, some considerations are necessary.

First of all, I think we need to focus on the final aims of the new circular economies. Do we want to eliminate the greenhouse gases emissions? Do we want to reduce the use of land? Do we want to reduce the impact on biodiversity? Do we want to phase out poverty? Etc.

Then, we have to plan the best way to reach our goals.

I’m sure that with adoption of CE principles there would be improvements for the environment and, in general, for the economy with respect to the current situation. Yet, we could put all our attention on some predetermined aspects while excluding some others that could be of equal, or even more, importance. A CE may not necessarily be a dematerialised economy and a focus on recycling may distract from improvements in material efficiency or prevention of by-products generation.

Therefore, how sure are we that a CE is the best way to fulfil all our goals?

Here the LCA community comes into play. LCA is now a mature tool for analysing the environmental impact of anthropogenic processes. LCA has a wider perspective where all the phases of a product life cycle are scrutinized. Searching for crucial hotspots and the comparison of alternative pathways is the daily job of an LCA practitioner.

We therefore welcome the EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy and the political visions for a more sustainable future stipulated in the new EU-legislature. But we encourage the LCA community to contribute to the implementation of CEs, because our knowledge and expertise is needed, now more than ever.

Reference:

European Commission (2015). Press-release: Closing the loop: Commission adopts ambitious new Circular Economy Package to boost competitiveness, create jobs and generate sustainable growth, dec 2. 2015: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-6203_en.htm

Why a ‘shrinking’ technology will never dominate the marginal

May 10, 2016 by Jannick Schmidt

– The case of electricity mixes in consequential LCA

Have you ever doubted what to include in your technology mixes? What happens when a technology is dominating the mix of today, but we know that the technology will be phased out and reduced in the future?

To an extent the answer depends on your study. But the studies we perform are for decision support, where our clients need to understand the environmental impacts of a change in demand for the product under study. For such studies we need a consequential approach – a modelling approach in which activities in a product system are linked so that all activities that are expected to change are included.

At the core of the consequential LCA are the marginal suppliers. They are defined as the ones being installed as a consequence of a change in demand (in increasing and stable markets, which is the general case for most products). You can read more details about marginal suppliers at www.consequential-lca.org.

Here, let us look at a concrete example. In our Energy Club we developed consequential LCIs on electricity for more than 20 different countries and regions (contact us for availability of these data). In these LCIs we base the identification of the marginal suppliers on the above reasoning. So the marginal electricity suppliers are those that are predicted to increase their installed capacity. The only exception is when they are constrained. That could be by a dependence on an input of a waste or by‐product or if the increase is fixed by legislation or other factors not related to changes in demand. Technologies with declining trends are not regarded as being part of the marginal.

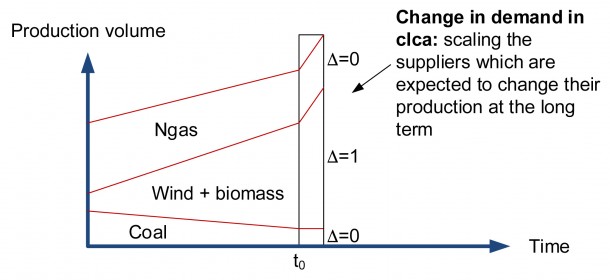

For instance, we found that the suppliers in Denmark that are predicted to increase capacity are wind and biomass; while coal is a decreasing (old) technology. This means that wind and biomass are marginal, while coal is not part of the marginal. See the figure below.

Any timing of the phasing out of technologies, such as coal, can provide a little flexibility and thereby make it a small part of the marginal, but never a significant part. Situations with flexibility could be:

‐ When there is a significant amount of overcapacity of the old technology

‐ In very short periods of time, to solve short‐term (quarters of years to entire years) need for capacity.

But still the shrinking technology will never dominate the marginal. This is because the timing of the phase out of old technologies is predominantly determined by other factors than changes in demand. These other factors include the life time/replacement rate of the technology as well as the economic performance compared to the new technologies that are installed.

Reference:

Muñoz I, Schmidt J H, de Saxcé M, Dalgaard R, Merciai S (2015), Inventory of country specific electricity in LCA ‐ consequential scenarios. Version 3.0. Report of the 2.‐0 LCA Energy Club. 2.-0 LCA consultants, Aalborg

It is not about money!

April 7, 2016 by Bo Weidema

The first working draft for ISO 14008 on monetary valuation of environmental impacts has now been sent out for commenting among the standardisation body members. The chair of the ISO Working Group is Bengt Steen, who already in the early 1990’ies introduced monetary valuation to Life Cycle Impact Assessment with his EPS method.

In the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) community there is a growing awareness that valuation is needed, and that the “ban” on weighting for comparative assertions that was introduced in the ISO 14044 LCA standard is not a viable position. Valuation serves the purpose of facilitating comparisons across different environmental midpoint impact categories, by applying weights (values) that reflect their relative importance (ISO 14040). Without valuation it becomes impossible to recommend the best decision when the options score best on different impact categories.

But not everyone is comfortable that monetary valuation is the best answer. In their recent expansion of the European Union Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) pilot tests to include a comparison of results when using different forms of weighting, monetary valuation methods were explicitly excluded, stating that “monetisation approaches (e.g. EPS2000, STEPWISE), will have to be dealt with separately”.

This leads me to highlight some frequent and important misunderstandings about monetary valuation, and here I first have to say: It is not about the money! Most of the criticism of monetary valuation applies to any form for valuation, including that of panel weightings and distance-to-target methods:

The values discussed in monetary valuation (and in comparative valuation in general) are the marginal values referring to trade-offs between alternative resource allocations, not the general moral values like the general value of democracy or the value of human life as such, that cannot be subject to quantified measurement and trade-offs. Much critique of monetary and marginal valuation comes from a confusion of these two types of values.

Valuation is often criticised for being anthropocentric. This critique is correct, but it is also irrelevant in its essence. Valuation has to be anthropocentric, since its purpose is to support human decision-making. Any concern for other species (or for that matter for any other group than the one that has the power to take the decision) must necessarily come as a concession from those who perform the valuation. However, the fact that it appears very difficult – or rather impossible – to design a truly non-anthropocentric valuation scheme, does not make it unimportant to raise the issue and seriously contemplate its relevance when deciding on the design of a valuation method. It should also be noted that an anthropocentric valuation does not necessarily imply a low valuation of nature; nature does have high value for humans, both use value (today often referred to as ecosystem services) and non-use values (existence value and bequest value).

Monetary valuation is also criticised for giving more weight to people who have more money. While this critique may seem intuitively correct, it is not true if equity-weighting is performed correctly. A simple weighting proportional to the inverse of the income will ensure that the same impact will be weighted equally across all levels of income. More advanced, empirically determined utility-weights can be applied, which lead to larger weights to poor population groups than to richer. Such equity-weighting should also be applied if values are expressed in non-monetary units! Because it is about values, not about the money!

Money is just a unit of exchange. You could equally well use units of Quality Adjusted Life Years, happiness-years, eco-points, or “Environmental Load Units” (ELUs) as Bengt Steen suggested. It is not about the money or the unit; it is about making things comparable. However, research has shown that when people are asked compare two goods with a monetary equivalent, their answers are more egoistic – less altruistic – than when asked to compare the same goods in a context where money is not mentioned explicitly. So the unit does matter, but only in the sense that answers given in the two different contexts can only be compared after adjustment for the context-dependent bias. This is just one out of many biases that can be introduced when asking people about their values:

It is a widespread critique of valuation methods that they assume that participants exhibit rational, utility-maximising behaviour when making valuations, while empirical evidence show that people do not exhibit this rational behaviour, neither in normal market transactions nor in experimental settings, but are influenced by the framing of the decision situation. A large body of literature on behavioural economics suggests improvements to the survey techniques to control and adjust for the systematic biases caused by the contextual and informational setting of the valuation.

When comparing items for which trade-offs between alternative resource allocations are in reality being made, as is most often the case in LCA, the problem of choice is unavoidable, and an outright rejection of valuation – monetary or not – is not a viable position.

However, a lot of the criticism of current valuations is valid. Many current valuations suffer from insufficient inclusion of equity-weighting, from many of the unnecessary biases described above, and from unnecessarily high uncertainties. But these are problems that can be solved, that need to be solved, and that we are working on solving, both in the ISO working group on monetary valuation and in our new crowd-funded Monetarisation Club that I urge anyone with interest in this development to join.