LCA for decision support

October 21, 2016 by Bo Weidema

Today, I give a keynote presentation to the “LCA Food 2016” conference in Dublin, on the topic of “Potentials and limitations of LCA for decision support”. The below figure is taken from one of my slides.

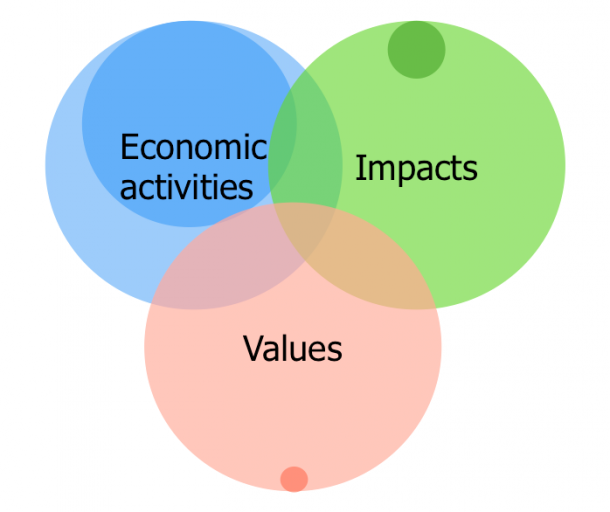

The three circles in the figure show our current knowledge, and the smaller circles within each illustrate how much of this knowledge is typically used by current LCA practice.

A wealth of knowledge is available for and from Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) as it combines three areas of knowledge:

- Knowledge on how supply and demand for products change the flows of products between economic activities (blue). Completeness is ensured by the use of IO-databases, based on data from national statistical agencies, and rebound effects are included based on marginal consumer behaviour. But many practitioners still do not use IO-databases in the background, resulting in up to 50% incompleteness in typical LCAs. Also it is still not common LCA practice to include the rebound effects, which can really change a result from beneficial to not or vice versa.

- Knowledge on the impacts from these activities on our natural, social and economic environment (green). Interdisciplinary research tells us what is the global annual loss of habitats, the global burden of diseases and social impacts, and the causal pathways from the human activities. Yet, most current LCAs are still limited to a few selected impacts on nature and human health, that account for maybe only 10% of the global impacts on the natural, social and economic environment.

- Knowledge on the values that humans place on and obtain from the existence and services of the environment and the economic activities (red). Welfare economics provides values (costs and benefits) expressed in comparable units of utility, including science-based equity-weighting and discounting. These values are based on market prices and survey data of representative selections of the relevant population. But most LCAs today are either presented in incomparable units or aggregated on the basis of the values of a small number of experts, mainly from westernized economies.

The above considerations can be extended to cover additional aspects of data and model quality, such as the models used for linking data into product systems, the spatial detail of data, the age of the data used, the transparency of the data, the data quality indicators used, and the review procedures applied. For all of these aspects, current LCA practice leaves much to be desired.

The main question for my keynote presentation is therefore: Why is most of current LCA practice so limited?

I have three suggestions for an answer to this question:

- Value of Information Analyses are generally not performed to identify the cost of additional information versus the costs of false negative or positive outcomes.

- Even when these costs are known, we still face the challenge of willful ignorance – the tendency that humans have to ignore information that does not fit with their prior worldview or interests. Willful ignorance is often caused by what you could call market failures, namely that:

- The ones who work with LCA – whether practitioners or decision-makers – often do not carry the (full) costs of making a wrong choice or of delaying a precautionary choice.

My conclusion is that for our knowledge to be used in practice, we need to make these costs matter to LCA practitioners and decision-makers, which means that we need to become involved in the power game around decision-making.

In this power game, we must not only provide knowledge but also empowerment of those stakeholders that have the winning (more environmentally friendly) solutions but currently have too low power to have them implemented. One powerful tool in this game is to call for due diligence by the more powerful players that have the losing (less environmentally friendly) solutions. Because these players are powerful, it may be necessary to find ways to temporarily compensate their losses, to ensure that the best possible compromises can be implemented. To maintain our scientific integrity, we need to lose our political virginity.